The Ideological Immune System:

Resistance to New Ideas in Science

by Jay Stuart Snelson

As our biological immune system protects our bodies from an invasion of foreign agents and pathogens, so does our ideological immune system protect our minds from an invasion of foreign ideas and doctrines. The history of the creation and disclosure of scientific ideas shows us that the more important, profound, and revolutionary a new idea, the more likely educated, intelligent, successful adults will resist understanding and accepting those new ideas. All of us have one: Our ideological immune system resists acceptance of any new ideas that would overturn any of our old basic ideas. Science is forever forging outrageous heresies that rock the boat of convention. It is the nature of science to give birth to foreign ideas that are alien to our sheltered ways of thinking. Should we allow our ideological immune systems to protect us? Or can we somehow suppress our ideological immune systems and embrace those ideas that are new and revolutionary. Do we have a choice, and if so, can science guide our choice?

For more than three centuries, the scientific method has been a peerless engine of discovery and invention. But no matter how profound the discovery or useful the invention, such advances are powerless to enrich humanity until their worth can be demonstrated to an influential audience. The history of science and technology is a record of the futility of new discovery and new invention without an influential backer to herald their worth. People are prone to value those things they are taught to value: the conventional and the familiar. Thus, new discovery needs a defender; new invention needs a champion.

Discovery and invention are often greeted as unwelcome intruders because they inaugurate new truth through new explanations of causality. A new truth may be seen as a new threat. Those threatened by new truth may ignore the truth, hide the truth, distort the truth, destroy the truth, or reject the truth to gain some perceived or real advantage. Those who attack, however, the most confirmed and verified truths, may not always do so out of fear. Their assault upon truth may be motivated by high ideals and a zeal for the preservation of some — as they perceive it — greater truth.

As the methods of science reward us with better explanations of causality, they give birth to new paradigms built on new validated truths. We are not surprised when these new truths are attacked by those who fear the advance of science or who, for an array reasons, may hold the scientist and his science in contempt. But we are stunned when those who honor science and its achievements (who may even earn their bread within the realm of science) attack the most verified and confirmed scientific truths. This is a curious aberration that demands an explanation.

The #1 Killer of Man

The short history of microbiology has given science an amazing account of an epic quest for truth that reveals the weakness of truth when it is without a successful champion. This pursuit of truth was aimed at discovering the causal factors that for thousands of years had given lethal vitality to the number-one killer of man. The search for the greatest mystery killer and the deadliest destroyer of human life since the Middle Ages, ended at the beginning of the 20th Century. And when the number-one killer of man was finally identified, no one would believe it.

The men who finally solved this profound mystery made a salient claim: this mysterious killer is a flying insect. The male is harmless, but the female bites into her victim to drink her victim’s blood. At the same time she injects her victim with “venom,” inducing a fever so agonizing that the victim craves only death. At the turn of the century, this explanation of causality sounded so bizarre that no one took it seriously. Indeed, if you replace the flying insect with a flying bat, it echoes Bram Stoker’s gory tale of the blood sucking vampire in his 1897 mystery novel, Dracula.

Aedes aegypti

(the yellow-fever mosquito)

Today these flying insects are taken seriously. They are identified in biology as Aedes aegypti (the yellow-fever mosquito) and her lethal cousin Anopheles (the malaria mosquito) As recently as the 1940s and 1950s, the Anopheles mosquito, by injecting her victims with malaria, caused the deaths of some three million people each year for 20 years. This adds up to a staggering sixty million deaths from malaria during just two decades (Nielsen 1979, pp. 428, 436). This grave statistic does not even include the millions of deaths caused by mosquito transmitted yellow fever.

“That Can’t be the Cause”

As essential as it is to scientific progress to apply scientific methods to identify causality, finding the correct identification alone is not enough to convince others that a new and superior explanation of causality has been found. Even when we have turned to science to understand the causes of those effects we most like and dislike, the struggle to understand causality and, thereby, optimize scientific progress has come in two steps. Each step involves solving an entirely different problem.

OPTIMIZING SCIENTIFIC PROGRESS (STEP ONE):

The true cause of any physical, biological, or social effect that we like or dislike must be correctly (scientifically) identified.

Where the aim is to optimize scientific progress, the importance of step one cannot be overstated. Grasping the correct understanding of causality is crucial, and yet, it is commonly overlooked, disregarded, or simply not taken into consideration in the first place. But even when step onehas been taken and the scientific evidence is overwhelming that the cause of a certain effect has been correctly identified, that is only part of the solution. In general, this new knowledge cannot be applied for the benefit of society untilstep twohas been taken:

OPTIMIZING SCIENTIFIC PROGRESS (STEP TWO):

Once the true cause of any effect that we like or dislike has been correctly identified, the identifier must convince others of its correctness when nearly everyone believes something else is the cause (usually the conventional explanation).

This second step toward the optimization of scientific progress is always a formidable problem to solve. It is often a step that must be taken along a path that is strewn with more hazards and pitfalls than the first step. Whenever the methods of science are applied to discover a new explanation of the causes of a certain effect, this implies there is now some old explanation of the causes of that effect. Those who have believed in the correctness of this older explanation of causality will not be quick to give up their belief. It is not merely some of them or many of them who will cling to the older explanation of causality — it is almost all of them, especially if they perceive themselves to be educated, intelligent, or successful. The central question to be answered here is why are people (especially, if they are educated, intelligent, and successful) inclined to cling to old and unsupported ideas of causality, when they could embrace new and supported ideas of causality? The answer is important. In this regard, here are three questions for the reader to consider:

- How would you rate your ability to accept any new minor idea that has a preponderance of scientific evidence to support it?

(1) below average, (2) average, (3) above average. - How would you rate your ability to accept any new major idea that has a preponderance of scientific evidence to support it?

(1) below average, (2) average, (3) above average. - How would you rate your ability to accept any new revolutionary idea that has a preponderance of scientific evidence to support it?

(1) below average, (2) average, (3) above average.

Throughout four centuries of modern science, when scientific investigators have put forth new explanations of causality — especially if they were revolutionary explanations of causality — the most common response has been: “That can’t be the cause!” This is not to say that every new explanation of causality has been, ipso facto, a better explanation of causality than the old explanation. Novelty is not the guarantor of a better idea. But more often than not, the new correct explanations of causality have been opposed with greater passion and vitriol than have been the new incorrect explanations of causality.

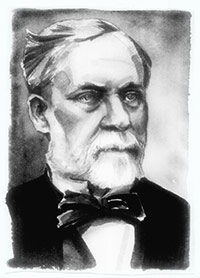

Carlos Finlay

This can be explained, in part, by examining the source of almost everyone’s fundamental beliefs on the causes of physical, biological, and social effects. What is the origin of the basic presuppositions, assumptions, and premises on causality (cause and effect) held by those people who perceive themselves to be educated, intelligent, or successful? When most people, upon hearing of a new scientific explanation of causality, have declared, “That can’t be the cause,” how did they arrive at this assertion? If all of the inputs that led to their respective assertions could be traced back to their sources, most commonly they would include: The book said, “That can’t be the cause.” My professor professed, “That can’t be the cause.” The authorities ruled, “That can’t be the cause.” Everyone says, “That can’t be the cause.” The experts agree, “That can’t be the cause.” Common sense tells me, “That can’t be the cause.” My intuition tells me, “That can’t be the cause.” I have a strong feeling, “That can’t be the cause.” Or some combination of these.

When new scientific explanations of causality have been observationally confirmed and verified, most people who have rejected these new explanations of causality have done so for no other reason than they differed with the old explanations. In general, people accept either what the old authorities claim are the correct explanations of causality or what their intuition tells them are the correct explanations. This common approach to understanding causality causes much misunderstanding. When the individual’s only means of identifying causality is based upon either authority or intuition, then a common effect is the acceptance of many misidentifications of causality. All misidentifications of causality present distortions of reality that lead to miseducation.

The misidentification of causality can be catastrophic. The incredible difficulty of tracking down the greatest mystery killer of all time — the mosquito — illustrates the awesome magnitude of such catastrophes.

Mosquitoes Attack Rome

Some historians claim the scourge of malaria was one of the factors leading to the collapse of the Roman Empire (Walker, 1955, p. 261). From the northern coast of Africa to the British Isles, malaria exacted its deadly toll across the expanse of the Empire. The Romans believed malaria was caused by the foul, gaseous, air that hovered around marshes, especially during warm weather. Our English word malaria is a contraction of the Italian mala aria meaning “bad air.” After the fall of pagan Rome, Christian Rome was no more secure from attack by malarian epidemics. During a conference of cardinals held at the Vatican Palace in 1623, eight cardinals and 30 secretaries were among many who were struck down and died of malaria (Walker, p. 262).

Malaria and yellow fever mosquitoes are tireless in their search for the blood of mammals and humans. Only the females suck blood, and the yellow fever mosquito has a special thirst for human blood to nourish her eggs. In their relentless search for human prey, the ever resourceful mosquitoes have flown aboard sailing ships to reach new lands and new victims. By this means, epidemics have quickly spread from port to port. (Until they arrived by ship in 1827, for example, there were no mosquitoes in the Hawaiian Islands.) The city of Philadelphia was hit with a yellow fever epidemic in 1793 that was reminiscent of a medieval plague. By the time the winter chill had throttled the epidemic, 4,044 Philadelphians were dead from yellow fever — one-tenth of the city’s population. Between 1793 and 1900, there were over a half million deaths from yellow fever recorded in the United States (Clark, 1961, p. 46). The effects of these epidemics were devastating, but what caused them? An army of experts were convinced they knew.

In the 19th century, medical experts believed yellow fever spread through the air from its source in sewage and the putrefaction of dead animals. In a similar way, experts believed that malaria spread through the air from poisonous marsh gas. By the beginning of the 20th century, this explanation of causality (for malaria) had been popular for several thousand years — since the time of the Romans and even earlier.

After thousands of years of misidentifying causality, an important step toward understanding this cause and effect relationship was taken by an American physician Josiah Clark Nott (1804–1873) who had a general practice in Mobile, Alabama. In 1848, Dr. Nott published a paper in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal in which he named various insects including mosquitoes as the probable carrier of both malaria and yellow fever. A major point of his argument was there were no known physical laws of gases that could account for the prevailing explanation for the spread of these diseases: by means of the transmission of poisonous vapors (“miasma”) rising from swamps (McCullough, 1977, p. 142). Nott reasoned, “…the morbific cause of Yellow Fever is not amenable to any of the laws of gases, vapors, emanations, etc., but has an inherent power to propagation, independent of the motions of the atmosphere, and which accords in many respects with the peculiar habits and instincts of Insects” (Chernin, 1983, p. 792). Nott’s biographer explains: “The main purpose of Nott’s article was to argue that the prevailing theory regarding malaria — that it arose from an emanation produced from the earth’s surface by decaying matter — was wholly inadequate to explain the propagation of yellow fever” (Horsman, 1987, l44). Today we know Nott was correct, but his novel explanation of the transmission of yellow fever and malaria was such a revolutionary departure from the old and accepted explanation that the important physicians of the time considered his explanation absurd (Walker, p. 269).

Nott’s conclusions were based upon years of scientific observation, but he did not offer controlled experimental evidence to prove that malaria and yellow fever are carried by infected mosquitoes. Nott presented his 1848 article on disease transmission a decade before Pasteur disclosed his germ theory. Nott’s novel conclusions might have been more influential if Pasteur’s germ theory had already gained acceptance. But revolutionary ideas are forever greeted as foreign ideas. When Pasteur introduced his revolutionary theories of disease transmission, they were backed by the full weight of experimental confirmation. Nevertheless, Pasteur’s irrefutable conclusions were callously ridiculed by physicians and scientists of his time. (Keim and Lumet, 1914, p. 114).

After Josiah Nott’s 1848 publication, thirty-three years marched by while the mosquitoes continued killing more victims. Then, in 1881, another important discovery was announced. A physician and epidemiologist, Dr. Carlos J. Finlay (1833–1915), had been conducting experiments in Havana, Cuba, aimed at identifying the cause of yellow fever. Every year since the founding of Havana more than three centuries earlier, the city had been hit with an epidemic of yellow fever.

Finlay reached the conclusion that the transmission of the deadly yellow fever is caused by the bite of a mosquito. Significantly, he held that it was not the bite of just any mosquito. This was an important breakthrough. There are some 3,000 different species and subspecies of mosquitoes (800 species were known in Finlay’s time), but only one of the 3,000 can transmit yellow fever from old victim to new victim. Dr. Finlay identified the specific killer mosquito as the female of the species Aedes aegypti. (It was not learned until many years later that “jungle yellow fever” is carried by certain other mosquito species.)

Finlay accomplished step one toward scientific progress. He correctly (scientifically) identified the true cause of the effect. The effect he identified the cause of is the vector or means of transmission of yellow fever. A superlative beginning, but if Finlay remained the only one who knew the true cause of the transmission of yellow fever, then the epidemics would continue to devastate the populace.

Step one, understanding causality, is an essential element of progress, but alone it’s power to advance progress is like that of an engine without fuel. The power is only potential; and potential power moves nothing. The missing element was step two: the identifier of causality must convince others of its correctness when nearly everyone believes something else is the cause.

Dr. Finlay would have to tell someone else of his discovery. His problem was how to convince the medical and health professionals that the mosquito transmitted yellow fever from old victim to new victim when everyone believed something else transmitted yellow fever. With this important goal in mind, Carlos Finlay journeyed to Washington, D.C. to attend the 1881 meeting of the International Sanitary Conference to disclose his findings. What presuppositions and premises did the physicians and health professionals at this conference hold on the transmission of disease?

The Germ Theory Delay

A decade earlier during the Franco-Prussian war, (1870–1871), the French chemist, Louis Pasteur, used his influence to encourage military surgeons to boil their scalpels and instruments and steam their bandages to kill germs as a practical means of preventing the spread of disease. The surgeons were skeptical. Germs can’t be the cause of disease, they said. Of the 13,173 amputations of arms, legs, fingers, and toes performed by the French Army during the war, 10,006 — more than three quarters — of these proved fatal to the amputees (Nuland, 1988, p. 373). Those few physicians, however, who did follow Pasteur’s advice obtained remarkable results that saved many lives. Gradually, over decades, the physicians (especially the younger ones) accepted Pasteur’s germ theory. One of Pasteur’s biographers relates: “When he [Pasteur] despaired at convincing his colleagues at the Academy [of Medicine], he would address, over their heads, the young physicians and students who attended the meetings” (Dubos, p. 74).

A central conclusion of the germ theory is that disease is a “contagion” (from the Latin contagionem meaning “a touching”) transmitted, directly or indirectly, by “touching” the diseased victim. The great Scottish surgeon, Joseph Lister (182–1912), after reading in 1865 Pasteur’s Memoire sur las fermentation apelee lactique (“Memorandum upon so called lactic fermentation,” 1857) got the idea of eliminating germs during surgery by applying carbolic acid to surgical instruments, dressings, and the surgeon’s hands. Between 1867 and 1869, Lister applied his new antiseptic techniques during 40 amputations. The results were startling: 34 of these amputees survived. Before Lister’s use of antiseptic surgery, most of his amputees died of postoperative infection. A high death rate had been the unhappy experience of other surgeons after performing amputations (Wood, 1948, p. 130). Lister’s development of antiseptic surgery was itself a revolution. In his February 13, 1874 letter to Pasteur, Lister showed his deep gratitude to his French colleague: “It would afford me the highest gratification to show you how greatly surgery is indebted to you.” In the same year, Pasteur was still trying to convince the surgeons at the French Academy of Medicine to sterilize their instruments with flame before using them in surgery (Vallery-Radot, 1920, pp. 238–240). Gradually the germ theory gained new adherents as it was embraced by younger students while its older detractors died out.

Louis Pasteur

At the 1881 sanitary conference, Dr. Carlos J. Finlay read a scientific paper to the learned men of medicine and biology. His paper was entitled: “The Mosquito Hypothetically Considered as the Agent of the Transmission of Yellow Fever.” Because Finlay was speaking before the International Sanitary Conference, he was confronted with an immediate problem. To these conference members, sanitary meant the absence of all agents of infectious disease. The conference members had come to believe (or had been schooled to believe) that yellow fever is an infectious disease that is transmitted by one thing: POOR SANITATION!

Finlay explained that yellow fever is not a contagious or infectious disease. It is not transmitted by poor sanitation. It is not even transmitted by direct contact with the victim. Yellow fever, he said, is transmitted by the bite of a female Aedes aegypti (at this time named Stegomyia fasciata) mosquito. Finlay emphasized that you can be living in a completely sanitary environment, but if you are bitten by a mosquito infected with yellow fever, you will contract the disease (if you are not immune from an earlier attack). The learned gentlemen attending the sanitary conference agreed: The mosquito can’t be the carrier of yellow fever.

In 1881, this was a revolutionary idea on the cause of disease transmission. A revolutionary idea (both then and now) is an idea that is a great turnaround from an established idea. The history of scientific revolutions reveals that the greater the intellectual revolution, the greater the opposition to that revolution. Dr. Finlay was successful by 1881 with step one: He achieved a correct identification of causality. But at step two, when he tried to convince others, his explanation of causality was rejected. How serious was this rejection? For those who lived where yellow fever epidemics were routine, it was very serious. These medical experts rejected as absurd the scientifically precise identification of the true cause (vector) of the number-one killer of man. These experts were prevented by their ideological immune systems from accepting Finlay’s revolutionary explanation of causality just as the experts of a generation earlier were prevented from accepting Pasteur’s revolutionary explanations of causality.

The Mosquito Men

Meanwhile seventeen more years elapsed while the ubiquitous mosquitoes continued to torment more victims with lethal injections of yellow fever. In 1898, the American politicians pushed the American citizens into a war with Spain. The United States Army was ordered to invade the Spanish-held island of Cuba. During the invasion most of the Americans “killed in action” were not killed by Spanish bullets; they were killed by Cuban-based mosquitoes. Even the generals behind the lines were not safe. During the Cuban campaign, one third of the U.S. Army’s general staff died of yellow fever.

The loss of so many high ranking officers caught the attention of the generals in Washington. In 1900, the U.S. Army sent a commission to Havana to solve the yellow fever problem. Heading the Yellow Fever Commission was an army surgeon and bacteriologist, Major Walter Reed. His orders from the Surgeon General, George Sternberg, were: “Wipe it out, Major, before it destroys all of the American occupation force in Cuba, wipe it out if you can” (Dolan, 1962, p. 8).

Reed began the search for a solution with this fundamental question: What is the cause of this effect (yellow fever) that we dislike? In Havana, there was a European-trained physician who claimed he already had an answer to this question. Dr. Carlos Finlay explained to Dr. Walter Reed how the mosquito carries yellow fever from old victim to new victim. Finlay even gave Reed some tiny black eggs of Aedes aegypti and exclaimed to Major Reed, “these are the eggs of the criminal.” Reed’s response, in so many words, was the mosquito can’t be the cause.

The accepted medical wisdom of the time was that yellow fever is a contagious disease transmitted by direct contact with the victim or his clothing, bedding, or eating utensils. During epidemics, health authorities imposed rigid quarantines. Mail and freight were disinfected before delivery. Frightened people flung the clothing and bedding of victims into the streets where they were quickly consumed by great bonfires. Sometimes even the victims’ houses were incinerated in a futile effort to destroy what was thought to be the contagious agents (Nielsen, 1979, p. 436).

In 1898, the U.S. Army set up a yellow fever camp at the Cuban town of Siboney. Soon the yellow fever epidemic was spreading so rapidly throughout Siboney that in desperation the medical officer in charge of the camp, Major William Gorgas, ordered the entire village burned to the ground along with the valuable cache of medical supplies (McCullough, p. 413). All these frantic efforts to contain the spread of yellow fever failed because (as would be proven later) yellow fever is not contagious.

Walter Reed began his search for the cause of yellow fever with the presupposition that yellow fever is contagious. Reed and his staff of skilled researchers probed for a microbe that could be the contagious killer. Their microscopes revealed nothing capable of causing yellow fever. Reed made an exhaustive investigation of every possible causal factor he could think of, but the search was futile. He had pursued every avenue of inquiry except one: Test this novel and absurd idea of the Havana physician and epidemiologist, Carlos Finlay, that yellow fever is transmitted from old victim to new victim by the mere bite of a mosquito.

By this time, Reed and his staff had concluded that the carrier of yellow fever could be an insect. If it was an insect, it could be any one of thousands, the pursuit of which might elude them forever. Instead of taking on this immense task, Reed agreed to first test Finlay’s theory that the carrier of yellow fever was not only a specific insect the mosquito, but a specific species of mosquito: Aedes aegypti.

The testing of Finlay’s theory presented a formidable problem. It could not be tested with animals because animals cannot be given yellow fever. (Not until 1927 did researchers discover the rhesus monkey can contract yellow fever from the bite of an infected mosquito, Dolan, 1962, p. 190.) This meant experiments would have to be conducted to deliberately transmit yellow fever to humans by the bite of an infected mosquito. If Finlay had identified the true cause of the transmission of yellow fever, then these would be risky and dangerous experiments. Just how risky and dangerous? The statistical probability of surviving a yellow fever attack was not good. In 1898, two years before Reed’s investigations in Havana, a yellow fever epidemic struck Rio de Janeiro. The death rate of those stricken with yellow fever was 94.5%. Nearly every fever victim perished. In other yellow fever epidemics, a mortality rate of 85% was common. (During the 1878 yellow fever epidemic in Memphis, Tennessee, for example, people died faster than they could be buried. Those who were not too sick, fled the city in panic only to be refused help from their armed neighbors in the countryside. Ignoring the risk, an army of looters descended upon the deserted city. They ransacked businesses and dwellings from one end of Memphis to the other in search of riches that by then were guarded only by the dead and dying. Meanwhile, the promiscuous mosquitoes in search of fresh blood struck the looters as they had the townspeople. Many looters were felled by the fever and many died in agony still clutching their sacks of plunder [Dolan, pp. 28–29] ).

With full knowledge of the mortality rate of yellow fever victims, Reed conducted experiments designed to give his volunteers yellow fever. Fortunately, most of those who contracted yellow fever from the systematic bites of infected mosquitoes survived the ordeal. One who did not survive was a member of Reed’s own Yellow Fever Commission: Dr. Jesse William Lazear (1866–1900). (It is not known whether the lethal bite that killed Lazear was accidental or intentional.) Ironically, Dr. Lazear was the first member of the Yellow Fever Commission to believe in Finlay’s theory of mosquito transmission. His own death confirmed the truth of the theory that he had implored Reed to consider testing.

Walter Reed

Walter Reed’s carefully controlled and brilliantly conceived experiments proved conclusively that the carrier and transmitter of yellow fever was Aedes aegypti. In so doing, Reed also proved that Dr. Carlos Finlay (disparagingly named “the mosquito man” by his medical peers) was not a self-deluded crackpot after all. With this new understanding of causality, Reed tried to develop a safe vaccine for yellow fever. He tested his new vaccines on more volunteers, but the vaccines were not safe. Reed was not as fortunate with these last volunteers as he had been previously. Three of the seven volunteers who contracted yellow fever from these vaccines died of their fevers. Discouraged by these disastrous experimental failures, Reed gave up the search for a safe vaccine. There was only one apparent defense against yellow fever: kill Aedes aegypti before she launched another epidemic. This was no small task in 1900 before the development of effective chemical pesticides. This seemingly impossible assignment was given to Major William Crawford Gorgas (1854–1920). During the U.S. Army occupation of Cuba, Gorgas was the Chief Sanitary Officer. The difficulties were so formidable, even Reed is said to have told Gorgas, “It can’t be done” (McCullough, p. 415). With suggestions from Reed and Finlay along with ingenious inventions of his own, Gorgas, in just 90 days, led his men on a successful purge of Aedes aegypti throughout the city of Havana. The result was sensational. For the first time in three centuries, there was not one new case of yellow fever recorded in the city of Havana. The scientific evidence was now overwhelming: The mosquito was, without question, the carrier of yellow fever. Gorgas was given much attention for his victory over Aedes aegypti and the consequent defeat of yellow fever in Havana. By special act of Congress, he was promoted to Assistant Surgeon General of the United States.

In 1904, William Gorgas, now a colonel, was sent to Panama to become the Chief Sanitary Officer for the construction of the new American project to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. His assignment: Rid the Canal Zone of yellow fever and malaria.

Earlier a French company had spent six frustrating years attempting to build a sea level canal (without locks) across the Isthmus. From the very beginning there were so many deaths among workers and engineers from yellow fever and malaria that this became a major factor forcing the French to abandon their monumental project.

With the knowledge he had gained earlier, Gorgas formulated a plan to protect the canal employees from the deadly mosquitoes. He ordered protective screens to cover the windows of the worker’s living quarters. He requested men and equipment to drain swamps and dry up mosquito breeding grounds. Where swamps could not be drained, Gorgas ordered kerosene to be sprayed on the water’s surface to smother the mosquito larva. (American entomologist, Leland O. Howard, first suggested using this method of mosquito extermination in 1892.) Gorgas sent all these requests for the necessary men and supplies to the Isthmian Canal Commission in charge of building the canal. To his great dismay, something went wrong. The Canal Commissioners responded to Gorgas by ignoring his requests, or by rejecting his requests, or by drastically limiting the quantities of materials sent. In short, the Canal Commissioners refused to cooperate with Gorgas and his plans for mosquito control. The question for us to consider is why.

From the beginning of his assignment, Gorgas told the Commissioners that the men, equipment, and supplies he had requested were necessary to kill off the deadly mosquitoes. The Commissioners believed differently. They were certain Colonel Gorgas was wasting his time and government funds by chasing mosquitoes across the Isthmus when he should be attending to the sick and dying workers. Gorgas explained that the mosquitoes were the cause of the disease and the deaths. The Commissioners answered with confidence: Yellow fever and malaria are caused by men who live and work in filthy, unsanitary, conditions. They were positive the mosquitoes had nothing to do with the growing epidemics of yellow fever and malaria.

Ironically, there was one item requisitioned by Gorgas the canal commissioner filled without complaint: coffins! The commissioner supplied Gorgas with every coffin he ordered. They even sent him extras. He needed them (Dolan and Silver, 1968, p. 142).

Gorgas warned the Commissioners that if they refused to give him the men and supplies necessary to exterminate the mosquitoes, the canal workers would be vulnerable to an irrepressible epidemic. The Commissioners continued to ignore Gorgas and his warnings with devastating results. A raging epidemic of yellow fever and malaria hit the canal workers and engineers. Mosquitoes were killing workers faster than they could be replaced. The frightening number of deaths caused workers to quit in panic. Three quarters of the American workers fled the canal.

Once the Canal Commissioners finally realized the entire canal project was in jeopardy of floundering, they acted quickly. The Commissioners sent urgent appeals to Washington to fire Gorgas. In their communications, they accused Gorgas of being an incompetent health officer, and blamed him for the ruinous spread of yellow fever and malaria.

In Washington, President Theodore Roosevelt was advised by the Secretary of War and other important officials to dismiss Gorgas. Roosevelt hesitated. The canal was his cherished project and he wanted to make the right decision. He wrote for advice to Dr. William H. Welch, Dean of Johns Hopkins Medical School. Welch advised that “no one else is as well qualified to conduct this work as the present incumbent, Dr. Gorgas.” Still hesitant, Roosevelt sought guidance from a close personal friend, Dr. Alexander Lambert, who told him, “Mr. President, upon what you decide depends whether or not you are going to get your canal. If you fall back upon the old methods of sanitation, you will fail, just as the French failed. If you back up Gorgas and his ideas and let him make his campaign against mosquitoes, then you get your canal” (Gorgas and Hendrick, 1924, pp. 198–201).

Roosevelt issued an immediate order to the Canal Commission to give their complete cooperation to Colonel Gorgas in the execution of his duties as Chief Sanitary Officer (Dolan and Silver, 1968, p. 168). Under orders from the President — but still with great reluctance — the Canal Commissioners provided Gorgas with all of the men, equipment, and supplies he had requested in the first place. Gorgas, understanding causality, wasted no time in marshaling his men, equipment, and supplies for the successful purge of malaria and yellow fever mosquitoes throughout the working and living areas of the Canal Zone. No surprise to Gorgas, the fatal epidemics ended and the Canal Commissioners built their grand monument to science and engineering: the Panama Canal.

Lessons From History

There are important lessons to be learned from the sequence of problems that had to be solved that led ultimately to the identification of the true causes of yellow fever and malaria, and the effective utilization of this new knowledge. Whether the realm of knowledge concerns physical action, biological action, or human action, when the goal is to optimize some major positive goal or to optimize the solution, then five sequential problems must be solved.

The first problem was identified two thousand years ago by the Roman poet Ovid, when he proclaimed: “The cause is hidden, but the effect is known.” Our fellow humans show exceptional ability when they are asked to identify all of the myriad physical, biological, and social effects they either like or dislike. They like good health and dislike disease. They like prosperity and dislike poverty. They like peace and dislike war. They like freedom and dislike slavery. The growing tally of effects that good people like and dislike is endless. As Ovid says, the effects are known. But what about their respective causes? Can they be easily identified?

UNDERSTANDING CAUSALITY, PROBLEM ONE: The true causes of the physical, biological, and social effects people most like and dislike are almost always hidden from view.

The cause of malaria remained hidden from view for thousands of years after that disliked effect was first observed. The cause of yellow fever remained hidden from view for hundreds of years after that even more feared and disliked effect was first noticed in the 15th Century. After Reed’s research proved the mosquito was the carrier of yellow fever, the actual infective agent that enters the blood stream of the victim through the bite of the mosquito was still hidden from view. Reed and his staff made a relentless microscopic search for the specific agent, but they never found it. As it turned out, they never could have observed it. Their optical microscopes (the best available at the time) were not powerful enough to see the causal agent. It was not until the development of the electron microscope in the 1930s by Vladimir Zworykin, James Hillier and others that the yellow fever virus was finally observed.

UNDERSTANDING CAUSALITY, PROBLEM TWO: Humans almost always misidentify the causes of the physical, biological, and social effects they most like and dislike.

There are few biological effects in history that have been more disliked than yellow fever and malaria. Before the rise of modern science, the “wrath of God” took the brunt of the blame. The Greek physician Hippocrates (460?–377? B.C.), author of the oath of fidelity (Hippocratic oath) still affirmed by modern physicians, claimed that malaria was caused by the drinking of stagnant water (Walker, p. 262). The French word for malaria, paludisme, means “marsh fever.” The belief that poisonous marsh gases and vapors caused malaria prevailed for thousands of years. Yellow fever, it was believed, was caused by putrefaction, and after the popularization of Pasteur’s germ theory in the second half of the 19th Century, that it was caused by poor sanitation. Others were convinced yellow fever and malaria were visited upon those with loose morals. Those who gambled in casinos, frolicked in brothels, or swilled sauce in saloons were believed to be the most vulnerable due to their moral decay.

UNDERSTANDING CAUSALITY, PROBLEM THREE: Because progress is built upon a correct (scientific) identification of the causes of physical, biological, and social effects, the problem is how to attain a correct identification of the causes of these effects.

Walter Reed employed the methods of science to identify and prove that the Aedes aegypti mosquito is the causal factor in the transmission of yellow fever. Two years earlier the British physician, Ronald Ross (1857–1932), employed the same methods of science to identify and prove that the Anopheles mosquito was the causal factor in the transmission of malaria. The grand solution to problem three is to apply a scientific approach to the identification of causality.

Significant progress toward the protection of men, women, and children from the effects of yellow fever and malaria could not (and did not) take place until the cause of the transmission of these diseases was correctly identified.

UNDERSTANDING CAUSALITY, PROBLEM FOUR: There must be someone with the resolve to continue pursuing the correct identification of the causes of the physical, biological, and social effects they like or dislike until the correct identification is attained.

Walter Reed possessed the will to continue in pursuit of a difficult goal (the identification of the yellow fever vector) and to overcome much failure and great discouragement until success was achieved. Before Reed, Dr. Finlay had the same resolve. Finlay failed to prove the correctness of his own mosquito theory, in part, because he was experimenting with animals all of which were immune to yellow fever. When Finlay experimented with mosquitoes biting yellow fever victims and then healthy persons, he was unable to confirm the transmission of the disease experimentally. Reed also experimented with humans. After many initial failures, he was finally successful in getting mosquitoes to transmit yellow fever from old victim to new victim, proving the correctness of Finlay’s theory. Reed, with important inputs from Dr. Henry Rose Carter, had determined the time pattern of infection that Finlay had missed (Gibson, 1950, pp. 65–68). A mosquito only becomes infected when it bites a fever victim between the third and the sixth days of infection, and only becomes dangerous after it has been infected for an “extrinsic incubation” period of at least 12 days before it bites a new victim (Clark, p. 61).

Carlos Finlay presented his theory of mosquito transmission to an international audience at Washington, D.C., in 1881, and to the Royal Academy of Havana in the same year. His theory was opposed and ridiculed by his medical peers (Clark, p. 53). It is important to note, however, that Finlay did not give up his experimental attempts to prove his theory during the next 19 years. In the end, his relentless determination enabled him to finally get the attention of Walter Reed who, like everyone else in medicine at the time (1900) who had heard of Finlay’s mosquito idea (including William Gorgas), thought the whole idea absurd.

UNDERSTANDING CAUSALITY, PROBLEM FIVE: There must be someone with the will to promulgate the new identification of causality until there is general acceptance of it by those who perceive themselves to be educated, intelligent, or successful.

William Gorgas proved the correctness of the mosquito transmission theory in a dramatic way with his successful campaign to eliminate yellow fever in Havana. He continued to promulgate this new explanation of causality with his important work in Panama. Because he refused to give up in the face of great opposition, his ultimate success made it possible for a growing number of educated, intelligent, and successful people to accept the revolutionary ideas of Finlay and Reed on the transmission of yellow fever by the mosquito.

The general acceptance of a new basic idea on causality may take decades, centuries, or millenniums. Nearly 1,500 years ago a physician from India wrote a paper on malaria and its cause. He identified the carrier of malaria to be a tiny flying insect — the mosquito. The physician was Susruta, who flourished in the 5th Century (Walker, p. 261). At the time his idea of causality did not make a sufficient impact and was soon forgotten.

More than 13 centuries later the American physician, Josiah Nott, published several papers in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal. He claimed that malaria and yellow fever are two different diseases and that they are not transmitted by poisonous marsh vapors but by insects and possibly mosquitoes. The learned men of medicine who read the paper agreed: That can’t be the cause of transmission. Thirty-three years later the Cuban physician, Carlos Finlay, who never heard of Susruta or Nott, published a paper naming a specific mosquito species as the carrier of yellow fever. Finlay was ridiculed by the professionals in medicine for the absurdity of his idea.

After the experimental achievements of Reed and his staff, the scientific evidence corroborating Finlay’s mosquito theory was indisputable. In spite of the overwhelming evidence, the experts, along with those they influenced, rejected the correct explanation of the cause of the number-one killer of man. Meanwhile millions of mosquitoes continued to inject millions of victims with their deadly venom of malaria and yellow fever. Many deaths from yellow fever and malaria could have been avoided, but the experts, the authorities, the educated, all agreed: The mosquito can’t be the cause of these frightful epidemics. Their rejection of demonstrable truth remains one of the great catastrophes in the history of human action. Their actions give rise to this paramount question: Why do most people refuse to accept new revolutionary explanations of causality, especially when these explanations are supported by a preponderance of scientific evidence?

The Canal Commissioners were immune to acceptance of the revolutionary and foreign theory of disease communication developed by Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed and confirmed by Reed, Gorgas, and others. Like the commissioners, each of us has an ideological immune system:

Our ideological immune system resists acceptance of any new ideas that would overturn any of our old basic ideas.

In other words, our ideological immune system repels any new ideas that do not agree with our previously accepted premises, presuppositions, and preconceptions (old ideas). When someone offers a new explanation of causality, usually our first reaction is to think: That can’t be the cause. Why? Because we were taught earlier that something else is the cause.

None of us like to give up our basic premises. If the truth of one of our fundamental premises is challenged, we tend to think and act as though we are under personal attack. When this happens, the goal is seldom to find truth. The goal is to defend our premises. When the primary goal becomes defense of our premises, whether they are true or false is not even a factor of consideration. Our goal becomes defense for the sake of defense.

The Isthmian Canal Commissioners refused to cooperate with Colonel Gorgas and his request for the men, equipment, and supplies necessary to protect the workers from the deadly mosquitoes. As a result, the mosquitoes caused a raging epidemic of yellow fever and malaria. The Commissioners responded to this catastrophe by blaming Gorgas for the epidemics. Their failure to understand causality was complete.

What went wrong? Were the engineers who sat on the Canal Commission dull, stupid, men? It is compelling to conclude they were merely dense blockheads, but that conclusion alone prevents us from learning the causes of their blunder. Stupid men lack intelligence and reason. Stupid they were not. Nonetheless, in spite of their intelligence and their reasoning ability, they got stuck defending false premises and false doctrines.

Scientific Skepticism

It is important to note the chronology of events before the appointment of Gorgas to the post of Chief Sanitary Officer for the Panama Canal project. On February 6, 1901, Dr. Walter Reed presented the results of the Yellow Fever Commission to the Pan American Medical Congress in Havana. The proof was incontrovertible: the mosquito transmits yellow fever and, therefore, yellow fever is not a contagious disease. In the same year William Gorgas was successful in purging the yellow fever mosquitoes from Havana. The result was spectacular: There was not one case of yellow fever in Havana in 1902. This brought to an end the annual yellow fever epidemics for the first time since the city’s founding over three centuries earlier. In the same year (1902), Ronald Ross was awarded the prestigious Nobel Prize in medicine for his brilliant detective work that led to his identification in 1898 of the Anopheles mosquito as the carrier of malaria. Gorgas was then honored by Congress for his eradication of yellow fever in Havana with his appointment to Assistant Surgeon General. Then in 1904, he was appointed Chief Sanitary Officer, Isthmian Canal Commission. In spite of his great prestige by 1904, and the overwhelming evidence verifying the mosquito theory of transmission, Gorgas could not convince the Canal Commissioners that the mosquito is the cause of the transmission of yellow fever and malaria. The Commissioners clung to their belief that yellow fever and malaria are caused by human exposure to filthy conditions of sanitation. They all agreed: The mosquito can’t be the cause. The President of the Canal Commission, John G. Walker, arrogantly dismissed the entire theory of mosquito caused disease in a word - “balderdash!” (McCullough, p. 422). Canal Commissioner and Governor of the Canal Zone, George W. Davis, was no more receptive when he chided Gorgas: “I’m your friend, Gorgas, and I’m trying to set you right. On the mosquito you are simply wild. All who agree with you are wild. Get the idea out of your head. Yellow fever, as we all know, is caused by filth” (Sullivan, 1927, p. 460).

The Canal Commissioners were overwhelmed by their ideological immune systems. These systems protected them from their acceptance of a revolutionary explanation of causality. And while the Commissioners were blocking the success of Gorgas in destroying mosquitoes, at the same time they were blocking their own success at building the canal. For them, their ideological immune systems become a cause of self-defeat. If the Commissioners had not been ordered by President Roosevelt to cooperate with Gorgas, the mosquitoes might have defeated the Americans in Panama as they did the French a decade and a half earlier.

Planck’s Maxim

In Germany during 1900, the same year Reed was sent to Havana, Max Planck (1858–1947) was introducing a revolution in physics known today as the quantum theory. His new theory explored this question: In the realm of physical action, how can we understand the causes of microcosmic effects in the very small world of subatomic particles? After 36 years of attempting to explain the quantum theory to his peers and fellow scientists, in his Philosophy of Physics, Planck reached a conclusion that deserves “maxim” status. (p. 97):

An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: it rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul. What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out and that the growing generation is familiarized with the idea from the beginning.

Fortunately for Max Planck, he lived 47 years after his 1900 disclosure of quantum physics. During this time he saw the majority of the opponents to his quantum theory “gradually die out.” Their ideological immune systems guarded them throughout their adult lives from Planck’s revolutionary ideas. But before his death at the age of 89, Planck had the satisfaction of witnessing several generations of young physicists embrace his quantum theory. The history of human action confirms Planck’s conclusion, restated as Planck’s Maxim:Educated, intelligent, successful adults rarely change their most fundamental premises.

The causes of this human phenomenon are manifold, but here are three principal causes for the reader to consider. The first involves a principle of human action:

(1) PRINCIPLE OF INTELLECTUAL INDOLENCE: It always takes more time and effort to embrace a new idea and less time and effort to cling to an old idea.

Our English noun “indolence” is derived from the Latin indolentia meaning “freedom from pain.” The indolent person prefers freedom from physical exertion, effort, unpleasantness, or pain. He also avoids mental exertion because that, too, is painful. By the time an individual is an adult, most (if not all) of his fundamental premises have had an authoritarian origin. The intellectual authorities in his life are the familiar teachers, professors, theologians, textbook writers, historians, journalists, physicists, biologists, et al. Once his fundamental premises have been accumulated through indoctrination during his formative years, he does not like to give them up. To do so, he must overcome the tendency to be intellectually indolent. This is always “painful.”

Medical historian and physician, Sherwin B. Nuland, has described the indifference and the hostility among established surgeons to Lister’s revolutionary development of antiseptic surgery: “Books have been written about why it was that the entire surgical world did not immediately embrace Lister’s teachings. One of the reasons is obvious: it was a great deal easier not to believe in them” (1988, p. 369).

Pasteur had little success converting his fellow members at the French Academy of Medicine to accept his germ theory. When success finally came, it was achieved with the young medical students who did not have to be convinced to give up their old ideas of disease transmission in favor of Pasteur’s new ideas. As the new generation of medical students accepted Pasteur’s germ theory, the older generation of physicians who had rejected Pasteur’s revolutionary ideas gradually died out. By the time these young students themselves matured into senior physicians, most of them would come to reject the new theory of mosquito transmission of disease. There were few conversions: these educated intelligent, successful adults did not change their most fundamental ideas on causality. To avoid intellectual exertion is natural, thus, the adult tends to cling to old basic ideas rather than give them up for new basic ideas. No exertion is required to maintain the ideological status quo. The principle of intellectual indolence is the foundation of the ideological immune system.

(2) FEAR OF REPUTATIONAL LOSS: When an individual�s reputation is built upon a foundation of certain basic premises, if the truth of these premises is challenged, his reputation is also challenged.

To defend his good reputation (a precious asset in most societies) the individual will defend his premises. To fail in the defense of his basic premises — as the defender usually sees it — is to lose his reputation. A loss of reputation means a loss of prestige and standing in those communities he deems important. Many people value their reputational status over their economic status.

Nuland gives another reason for the antagonism among surgeons to Lister’s great advances in surgical technology: “Imagine what it must have felt like for a surgeon to accept a theory that confronts him with the intolerable fact that for the previous fifteen years of his career he has been killing his patients by allowing into their wounds microbes which he should have been destroying” (p. 370).

(3) FEAR OF ECONOMIC LOSS: If the truth of an individual�s basic premises is inextricably tied to his economic well being, he will feel compelled to defend his premises as a means of defending his income.

If a scientist’s funding is based upon a hypothesis that cannot be confirmed — where a growing amount of observational data contradicts his hypothesis — he may be highly motivated to defend his hypothesis as the most expedient means of defending his funding. In such cases the quest for scientific funding may very well take priority over the quest for scientific truth.

Ideological Immunity

The magnitude and direction — the vector — of scientific progress is determined by the accumulation of better explanations of the fundamental causes of physical, biological, and social effects. Across the span of four centuries we have applied scientific methods to strengthen our understanding of causality. In so doing we have been steadily evolving Western society from a static society to a dynamic society. The prime feature of a dynamic society is the rapid acceleration of better explanations of causality. These advances in understanding produce rapid change across the entire fabric of social institutions. In a dynamic society those who maintain their immunity to new ideas — merely because they are new or revolutionary ideas — will pay a heavy price for their intractable rigidity. Those who are unable or unwilling to adapt to rapid changes will be left behind by the march of progress.

On the other hand, every student of the history of ideas knows that a new idea is not necessarily a better idea. To replace a superior old idea with an inferior new idea is never a good idea and is always intellectually and culturally regressive. The individual who prizes his intellectual integrity may want to strengthen his immunity to new bad ideas and weaken or suppress his immunity to new good ideas. This presumes, however, that a scientific standard of good idea versus bad idea can be found. How might the scientific skeptic in a dynamic society avoid being overwhelmed by his ideological immune system as were the Panama Canal Commissioners?

Defense from the indiscriminate protection of our own ideological immune system begins with the recognition that everyone has an ideological immune system that protects him or her from new ideas: new good ideas and new bad ideas. For the scientific skeptic who would avoid being overwhelmed by his ideological immune system, there is a scientific guideline to follow:

THE PRINCIPLE OF SCIENTIFIC SKEPTICISM: The less scientific verification for an explanation of causality, the more skeptical one can afford to be; and the more scientific verification the less skeptical one can afford to be.

If a new explanation of causality has been independently verified, confirmed, and corroborated with a growing amount of indisputable evidence to support it, you may want to give serious consideration to suppressing your immunity to its acceptance as a better explanation of causality.

In a dynamic society there will be a growing array of scientific disciplines generating new explanations of causality. No one will have the time or knowledge to test every new explanation of causality to determine if it is better than the old explanation. But the dynamic skeptic can make an effort to determine if those who have proposed and tested a new explanation of causality have applied the testing methodology known as the scientific method. The dynamic skeptic governs his ideological immune system. The static skeptic is governed by his ideological immune system. The choice is ours: to govern or be governed.

Bibliography

- Chernin, E. 1983. “Josiah Clark Nott, Insects, and Yellow Fever.” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Nov.,Vol. 59, No. 9,790–802.

- Clark, P. F. 1961. Pioneer Microbiologists of America. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Dolan, Jr. E. F. and H. T. Silver, 1968. William Crawford Gorgas: Warrior in White. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

- Dolan, Jr. E. F. 1962. Vanquishing Yellow Fever: Walter Reed. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica Press.

- Dubos, R. J. 1950. Louis Pasteur Free Lance of Science Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Gibson, J. M. 1950. Physician to the World: The Life of General William C. Gorgas. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gorgas, M. D. and H. Burton. 1924. William Crawford Gorgas: His Life and Work. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co.

- Keim, A. and L. Lumet. 1914. Louis Pasteur. New York: Frederick A. Stokes.

- Horsman, R. 1987. Josiah Nott of Molbile: Southerner, Physician, and Racial Theorist. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press.

- McCullough, D. G. 1977. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- Nielsen, L. T. 1979. “Mosquitoes, the Mighty Killers.” National Geographic, Sept., Vol. 156, No. 3, 427–440.

- Nuland, S. B. 1988. Doctors: The Biography of Medicine. New York: Knopf.

- Planck, M. 1936. Philosophy of Physics. New York: W. W.Norton. Translated by W. H. Johnston.

- Sullivan, M. 1927. Our Times, The United States, 1900–1975, The Turn of the Century.New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Vallery-Radot, R. 1920. The Life of Pasteur. London: Constable and Company Ltd.

- Walker, K. 1955. The Story of Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wood, L. N. 1948. Louis Pasteur. New York: Julian Messner lnc.

2 comments:

I think you should take up stamp collecting. Or go skiing again...

We know that you like to make out like you're a neanderthal but we know that you secretly enjoy a bit of mental exercise.

Post a Comment